Mr Adam's Chimneypiece

Throughout the second half of the 18th century the domestic interiors of Georgian Edinburgh were designed as perfectly contrived essays in elegance and refinement. Light, symmetry, and colour were the hallmarks of a style which adopted the tenets of ancient classicism, interpreting them in a modern form.

Yet this was northern Europe, and the citizens of the Scottish capital, with its unforgiving east winds and chilly winter mists, were practical in their approach to life. They may have gloried in fashionable illusions to the 'sublime', but they also needed comfort and, on the north facing slopes of the New Town, comfort meant warmth.

The architectural treatment of the fireplace, accordingly, gained a significance which it had never possessed in the villas of Greece or Rome, and it was to evolve within the constraints of the classical decorative tradition as the focal point of every room from the first floor 'piano nobile' to the upstairs bedrooms while at the same time developing the character of a distinctive folk art. In the hands of Edinburgh craftsmen the impeccably proportioned neoclassical chimneypiece of pine ornamented with gesso - essentially Spanish whiting fortified with a mix of glue size - rapidly became the architectural icon of the age. Some were simple, their decoration 'chaste' and understated; others were riotously elaborate. They were produced in enormous quantities for a discriminating public which was increasingly appreciative of quality, and their popularity as household fittings was to last three quarters of a century.

As far as the historical record is concerned, however, it was perhaps this very success which has left us with remarkably little detailed knowledge of their exact origins. Quite simply, since pine and gesso chimneypieces were made in large numbers, they were taken for granted, and the information which we now possess of their designers or the method of manufacturing and marketing them, tell us little or nothing of the men - perhaps even the women - involved in that production.

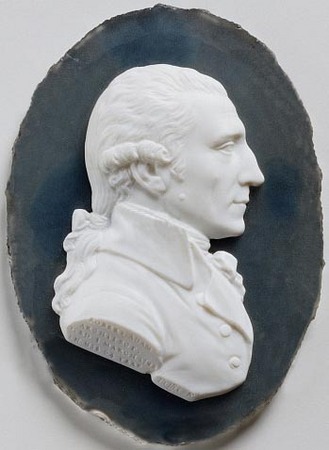

In attempting to solve the mystery of who produced Edinburgh's pine and gesso chimneypieces the most useful starting point is 1758, the year in which the young Scots-born architect, Robert Adam, returned from his grand tour of Italy and the Adriatic coast, and set about creating - in his words - ' a kind of Revolution' in architectural taste. Today Robert Adam is best remembered for such great houses as Syon, Keddleston, and Culzean, but the Adam revolution had another dimension. Where 'refinement' had once been the prerogative of a wealthy class, Adam's neoclassicism was to establish its appeal with a wider public, transforming the design of the most modest middle class houses, as well as stately homes.

The symbol which, above all others, was to characterise this radical change was the mantelpiece which bears his name. While Adam's wealthy patrons continued to favour expensive chimneypieces of monumental statuary marble, either inlaid or meticulously carved, there was another kind of demand on the rise, and it came from a burgeoning professional and merchant class which believed that it too had the right to aspire to good taste in architectural matters. This was a clientele of means, rather than a rich elite, and its spending power, while substantial, had its limits. Their number included artisans, clergymen, shopkeepers, professors, doctors, prosperous widows, and the sons of minor landowners. For them, neoclassicism symbolised cultural advancement and defined Scotland as a progressive country in the mainstream of universal enlightened learning. They had an appetite for the new vocabulary of neoclassicism, but usually on a budget, which meant that, inevitably, a technology was required which would supply them with competitively priced fittings for their houses. Robert Adam's 'corrected' style made this possible by introducing a taste for architectural ornamentation in shallow relief set against a plain background, rather than the decorative extravagance which the Palladians of his father's generation had inherited from their baroque predecessors. It was possible therefore to dispense with the time consuming work of the carver in lime wood or marble and develop a production line system of producing relief ornamentation in gesso ( or 'Adam's composition') which could then be applied to a prepared chimneypiece frame. Whilst this was substantially cheaper than the traditional alternatives, it would seem, from the profusion of mixed carved lime wood and gesso originals of the 1760s that the switch was not made overnight, and even when the all-gesso relief chimneypiece did eventually monopolise the market, there was clearly a determination to maintain a standard of design which would have satisfied the exacting requirements of the Adam drawing office.

Robert Adam's contribution to the development of a late 18th century aesthetic of architecture was considerable, yet it would not have been possible without the climate of change which had already taken place both before and during his four year absence. Edinburgh, liberated from the constraint - both actual and psychological - of a medieval city wall, had already set about asserting its status as an international city famed for its intellectual vigour. In the year of Adam's return, David Hume had published his 'Treatise of Human Nature' and was engaged on his monumental 'History of England'; Adam Smith was teaching at Edinburgh University, and writing his 'Theory of Moral Sentiments', William Robertson, cousin to the Adams, and later to become royal chaplain and principal of Edinburgh University, was finishing his 'History of Scotland'; Adam Ramsay, who had painted Adam's mother in 1754, had become established as the country's leading portrait painter.

The world was beginning to take note of such achievements, and the family practice had already benefitted from its architectural opportunities, having provided the city with a number of significant buildings, such as the Town Infirmary (1739, by William, father and founder of the architectural dynasty) and the city's Royal Exchange, by elder brother John, which was nearing completion in the year of Robert's return. Edinburgh had embarked upon an unprecedented era of expansion and development which was to be sustained for upwards of half a century, more than fulfilling the ambitions of earlier frustrated visionaries like the exiled Jacobite, the Earl of Mar, who was doubtless mindful of such Parisian glories as Marsart's Palace,Verdone when he published his 1728 plea for the improvement of his own decaying and congested native capital. The once prevailing view that the young Robert Adam was a mere provincial 'ingenue' whose brilliance could only flourish after leaving Scotland is no longer convincing, even though he himself was to rail against his native country as a 'narrow place' which offered limited scope for his ambitions. In fact the early Scottish experience, and the influence of Scotland's native building tradition, were critical factors in Adam's development.

Amongst the factors which made Edinburgh's transformation possible in Adam's day three were particularly critical. The first of those - the final defeat of the Jacobite forces at Culloden in 1746 - removed the latent insecurity which had curtailed the country's economic and social progress for generations, and ushered in an era of postwar confidence which invites comparison with the heady atmosphere of the Festival of Britain two centuries later. There was a widespread climate of optimism, a general determination to turn away from a troubled past, and forge a new kind of forward looking society.

The second factor was the one which expressed these aspirations and caught the mood of the moment perfectly. Sir Gilbert Elliott of Minto's 1752 'Proposal for carrying out certain public works in the city of Edinburgh' was to become the manifesto which made Adam's 'kind of revolution' possible. Though Elliott's thinking was largely based on the logic of an agricultural improver rather than a social reformer (Minto estate being among the first in Scotland to cultivate the potato on a large scale), his plea was impassioned and unashamedly patriotic, beginning with an account of the collapse of a six storey tenement, and the deplorable state of the city, going on to quote Andrew Fletcher of Saltoun who had lamented the 'poverty and uncleanliness' of Edinburgh at the close of the previous century, and drawing unflattering comparisons with fashionable London, Berlin and Turin.

Physical improvement and expansion argued Elliott, would have beneficial economic and moral consequences - 'The number of useful people will increase; the rents of land rise; the public revenue improve; and, in the room of sloth and poverty, will succeed industry and opulence'. His practical suggestions included the obtaining of ' an Act of Parliament for extending the royalty; to enlarge and beautify the town, by opening new streets to the north and south -' the city of Elliott's vision was a capital ' of learning and the arts, of politeness, and of refinement of every kind.'

The third factor contributing to the city's augustan metamorphosis - perhaps the most critical of all- was the availability of a highly skilled labour force drawn from all sectors of the building trade, the outcome, to some extent, of the Scots ethos of individual self advancement which laid an emphasis on training and education at almost every level of society. Scottish artisans were rigorously schooled in their respective crafts, and were expected to deliver a high standard of work. Their technical education was often complemented by instruction of a more high-minded sort, from the teaching of art, both practical and theoretical, had long been directed at the 'trades and manufacturers' with a view to strengthening the national economy. This was particularly the case after the traumatic Darien disaster of the 1690s, which had brought high risk investment into disrepute, and was further accentuated after the union of 1707, when national aspirations, circumscribed politically, were subsumed into a sort of patriotic commercialism. In 1728 the precociously intellectual John Clark of Penicuik had recommended setting up of an art academy with the specific aim of improving design in the linen industry. The following year Edinburgh's 'Academy of St Luke' was founded by, among others, William Adam, and by 1731 it was sufficiently well established to be granted rooms in the University where its pupils included the young Alan RAMSAY. Teaching was largely based on close copying of 'models in plaister from the best antique statues' and drawings, prints, and paintings by European old masters. In 1760 a formally constituted body, 'The Trustee's Academy', was set up with government funds which were largely drawn from the revenues of forfeited Jacobite estates - an interesting example of the State intervening in an economy long before the advent of development agencies and enterprise boards. As before, the emphasis was to be on the improvement of standards of design in the trades and in manufacturing industry with a view to developing exports, though the teaching of the 'higher arts' by masters of the calibre of William Delacou, Alexander Runciman, and David Allan would ensure that the creative imagination, as well as the practical skills of draftsmanship, had a role to play.

The response to Elliott’s idealistic blueprint for an improved and enlarged Scottish capital was to be one of positive enthusiasm, particularly from the city’s shrewd and influential Lord Provost, George Drummond. Within months of a body of commissioners (their number included the Duke of Argyll, and James Boswell’s father, Lord Auchinleck) had begun negotiations for land for a new Exchange. By August of 1753 Robert Adam’s brother John had produced a plan and the following month the foundation stone was laid. The significance of this was profound – in effect Edinburgh was making a bid to be taken seriously as a modern capital city – and the event was celebrated effusively in high-flown verse by the clergyman-playwright, John Home. His sentiments are revealing, with references to Caledonia ‘wrapt in Darkness’, her ‘Sons, despairing’ fled ‘To Climes remote’ as a sort of wandering tribe of mercenaries and colonists virtuously saving other nations, like Belgium and Sweden, while the ‘Hive at home’ languishes ‘Weak and Forlorn’, and at the mercy of barb’rous chiefs’. Then comes resurrection, as ‘Scotland’s Youth – Salutes the Dawning of a brighter Morn’. Hume’s panegyric continues, by way of exotic images os ‘Indians clothed from Scottish Looms’ and Scotland’s hills traversed by ‘Roman Ways’ until it reaches its crescendo – ‘Last of the Arts, proud Architecture comes, to grace EDINA with majestic Domes. BRITONS, this day is laid a PRIMAL STONE.’ Whatever its literary merits, Hume’s ecstatic hymn to progress brilliantly captures the atmosphere of a city in which, it seemed, almost anything might be possible in this imminent re-invented world of classical glory.

The construction of a prestigious new building within the city boundaries was one thing. The extension of the regality, however, took rather longer to accomplish. First of all, there were landowners and farmers who had to be persuaded to relinquish their fields; then developers and builders had to be encouraged to accept the viability of large scale investment in an untried project. The first breach in the city wall came in 1575 when Elizabeth, Lady Nicholson instructed the sale of feus for plots of building land in the parks around her house. These ‘Southside’ developments at first repeated the architectural formula of the medieval Old Town, which was dominated by rubblestone tenements, usually with projecting gables and turnpike staircases; by degrees, however, attempts at architectural experimentation began to emerge such as the coursed sneck and rubble chequered patterning of elevations by the mason builder Michael Nasmyth until the vocabulary of classicism began to assert itself hesitantly, with such stylish extras as venetian windows and ‘Gibbs’ doorways (named after William Adams Aberdeen born contemporary James Gibbs, a protégé of the Earl of Mar, and a friend of Christopher Wren). Internally, this change was even more pronounced; within each flat, the main rooms, grouped around a modest hall, tended to observe classical rules of design and taste; instead of the floor to ceiling wainscot paneling, and the simple bolection moulded fireplace of the congested ‘land’ of the High street, there was painted plaster, delicate cornice-work, symmetrical dado paneling and doors and – above all – an elaborately designed chimneypiece which was a direct adaptation of the architecture of antique Greece and Rome.

This was ‘Mr Adam’s Chimneypiece’, and it rapidly became the sine qua non of the fashionable streets and squares which spread rapidly southwards. In Italy and the Adriatic, in the company of such leading exponents of classicism as the engraver Piranesi and the artist Clerisseau, Robert Adam had honed his already considerable sense of the aesthetics of classicism to perfection. Added to the discipline which had already been passed on by his father, Scotland’s foremost Palladian architect, this enabled him to achieve his aim of revolutionizing public taste throughout Britain.

The underlying currents of neoclassicism were social, as well as visual, in so far as its emphasis on ‘refined taste’ as a universal benefit entailed broadening the base of its appeal downwards. In other words, good quality architecture was no longer to be the preserve of a wealthy elite, but was to be experienced by the population as a whole or at least those of middling means. In recognizing this architects like Adam were perhaps following a trend, rather than advancing a democratic cause, for by the second half of the `18th century the rise of the merchant, professional and artisan classes in Scotland was providing the focus of a revived economy previously dominated by a narrow and powerful feudal elite. The Adam family gift for combining pragmatic opportunism with visionary idealism was perfectly suited to such circumstances and they instinctively understood the demands of this new, essentially middle class clientele.

One factor which they quickly took on board, no doubt, was the need for rapid systems of production for building materials and architectural components. Their knowledge of the building business was intensive; William Adam senior had built up a commercial empire based on the ‘vertical integration’ of all its related parts; in 1714 he had co-founded Scotland’s first commercial brick and Dutch pantile works, and contracted the rights to win the required clay from the lands of Abbotshall, where he was also involved in coalmining. Throughout the 1720s and 1730s, when his reputation as an architect to the aristocracy was well established, he maintained such commercial and manufacturing interests, leasing the Cowgate leather yard as a coal depot, buying up warehouses in Leith, probably for the storing and processing of building materials such as Baltic timber and Italian marble, negotiating the rights to quarry stone at some of the best locations in Scotland, speculating in land (the site of fashionable George Square had even been in the family firm’s possession) and perhaps even brewing beer for his workforce.

This combination of hard-headed capitalism and an almost poetic sense of the aesthetics of architecture was a trait which passed down to the next generation – both James and Robert, for example, were directors of (and pattern designers for) the Carron Ironworks, which was founded in 1759, and produced the elegant foundry cast grates used in conjunction with the neoclassical chimneypieces. In this case, as in others, a simple principle applied. The sons were expected to develop a responsibility to a highly trained team of designers and overseers. In the Carron foundry designs in the Adam manner were to be produced by the talented Haworth brothers – and so convincingly, at times, that the precise authorship of a pattern can be impossible to determine. This system of business management was organized with almost militant precision, whereby the Adams entered the day-to-day supervision of their ‘regiment of artificers’ to a top tier of clerk –of-work, leaving themselves time to cultivate clients and expand the practice. On Robert Adam’s return from his grand tour the decision seems to have been taken to concentrate activities in London, and he settled there in January 1758, beginning a project for the redecoration of Hatchlands in Surrey, and sending for James and two of his sisters to join him. In England the brothers had less direct control over the quality of craftsmanship, and Robert complained about the ‘angry, stiff, sharp manner’ of southern workmanship. In Scotland, however, where the Adam practice had long enjoyed pre-eminence ( William Adam as King’s master mason, having been generally acknowledged as ‘the universal architect of the country’), there seems to have been a symbiotic sense of a common purpose which was shared by the architect brothers and their artisans and suppliers. The Edinburgh office, where Robert had started his architectural career at the age of eighteen after attending the University, was maintained under the direction of older brother John, Robert and James making annual visits in connection with Scottish commissions, and it is likely that the sort of architect-artisan relationship favoured by their father, who had boasted he was ‘bred a mason and served his time as one’ still applied.

In this context the sudden evolution of the ‘Adam’ chimneypiece as a standard fixture in the Southside could be advanced as the perfect example of the fusion of innovative technical skills and the imaginative creativity of an architectural theorist. This is not to say that the ‘classical’ chimneypiece, as such, was invented by the Adam brothers and some anonymous group of artisans in their service. A massive body of literature on architectural and decorative classicism was already available when the firm founded by William Adam was in its infancy, and even in remote Scotland the notion that ‘classical antiquity’ was synonymous with high culture had a long pedigree which, in purely architectural terms, had been meticulously analysed as early as 1452 by the great scholar and theoretician, Alberti. The Venetian Sebastiano Serlio had published his ‘Rules of Architecture’, in which the five orders were first codified, in 1537. A best seller in seven languages, Serlio’s book had a universal influence which was clearly evident in such ‘Scottish Renaissance’ masterpieces as George Heriot’s school and the original elevations of the old Parliament buildings. Engraved books specifically of chimneypieces, much influenced by the 16th century Italian Renaissance models, were being published in Paris in the 1630s by the architect designer Pierre Collot, and widely circulated; by the 1660s demand for the engraved designs of Jean le Pautre’s stylish Parisian chimneypieces in his Cheminees a la Moderne was so great that they were being pirated by print makers in Amsterdam. In Britain publications like Chambers ‘Treatise on Civil Architecture’, Darly’s ‘The Ornamental Architect’, Pain’s ‘Builders Companion’ and Batty Langley’s ‘ Treasury of Designs’ were all standard reference works by the 1770s. In his ‘Complete Body of Architecture’ of 1756 Isaac Ware had stressed the fundamental importance of the chimneypiece – ‘the first thing designed, and the fixed point from which the architect is to direct his work’ in the rest of the room. Ware also seemed to have a horror of the moral dangers that the wrong sort of chimneypiece might present, and firmly warned against ‘nudities – according to the present licentiousness of sculpture in the parlour of a polite gentleman’. The wide availability of printed information was complemented by a general awareness of the ‘superior qualities’ of classicism brought back by early grand tourists – their number included the ‘natural’ son of James IV, tutored by Erasmus in Padua, as well as an endless stream of Scottish ‘milords’. The built precedents for Scottish architectural classicism were plentiful by the time of Robert Adam’s birth. Sir William Bruce had introduced the first palladian scheme to Scotland (and the third in the United Kingdom) at his own house, Balcaskie, in the 1670s, went on to design the exemplary classical country seat for himself at Kinross, and was responsible for the main part of Hopetoun which was built between 1689 and 1703. James Smith had used the benefit of his travels oin the Continent at such houses as Newhailes, which was built in the 1690s. In the very year that Robert Adam was born the quintessential ‘Plinian’ classical villa, Mavisbank, was being completed by his father to the exacting requirements of Sir John Clark.

Classicism was not simply an architectural style which happened to fall into fashion. It represented a whole new system of values which provided the norms for civilized and enlightened living, embracing literature, the law, medicine, and education. It was perhaps a curious form of modernism which took, as its template, the styles and procedures of foreign and ancient civilizations but it was no less revolutionary for that. Why else should it set the tone for Scotland’s enlightenment, or the radicalism of Federal America, or aspiring Europeanism of Catherine the Great’s Russia? It was, in effect, the leitmotiv of the age of Voltaire, Rousseau, and Hume, with its emphasis on order, reason and harmony. A well organized neoclassical building combined function with a belief in the perfectibility of form. It was also a reaction against much that had gone before – ‘impure’ styles such as baroque, rococo and debased gothic which the 18th century modernists associated with decadence, corruption and superstition. While it might seem invidious to describe an architect like Robert Adam and his rival William Chambers as 18th century equivalents of Gropius and Le Corbusier, eager to sweep away the past and replace it with an ultra-rational vision of the future, the comparison is not entirely inaccurate.

Neoclassicism was to become a conquering force, setting the parameters of fashion in the first truly ‘international’ style. By the late 18th century, any member of the gentry who had failed to improve, if not rebuild, his house (a la mode) was probably regarded as quaintly old fashioned, embarrassingly impoverished, or both. While it was more or less mandatory for a successful Edinburgh lawyer or Leith merchant to set up his family in the pristine comfort of a well arranged neoclassical interior, even if he himself had been born and raised in rooms above some bustling wynd.

There was, of course, an innate contradiction in that neoclassicism, for all its clean lines and fastidious proportions, was essentially a modernism which derived its inspiration from the past. It appealed to the intellectual instincts of a cognoscenti which was immersed in the culture of Homer, Ovid, Vergil, and Pliny. In post union Scotland, there was also a pre-occupation with the precise nature of the Roman period, and a belief that, north of Hadrians’ wall, the frontier of the empire was no mere primitive outpost held by an army of unwilling recruits from Italy, Spain and Gaul whose sole purpose was the suppression of marauding tribes of Picts, but, on the contrary, was a sophisticated, well administered society in which peaceful trading and the pursuit of learning were commonplace. It became THE DUTY of the gentleman to demonstrate this belief by archeological example, wherever possible. Antiquarianism may have started as an eccentric fad but by the middle of the century it was a powerful force with formidable champions like Sir John Clark and the eleventh Earl of Buchan, and when one philistine landowner declared his intention to demolish the last complete Roman structure in the country – Arthur’s oven, a Mythraic temple near Falkirk – the outcry was as vociferous as John Betjeman’s enraged diatribe over the doomed Euston Arch (and , sadly, just as ineffectual).

This scholarly Scots passion for antique classicism also extended to Italy, where an expatriot colony of Scottish artists, ‘bear leaders’ (the self styled Ciceroni, or tour guides), dealers in antiquities, and gentlemen of means intent on self improvement made themselves at home amongst the ruins of the Eternal City, or wandered around the excavations of Pompeii and Herculaneum. The affinity which men like the diplomat Sir William Hamilton, the scholar-dealer James Byres, and the artist Jacob More had with their newly adopted country no doubt owed much to the increasing conviction that, as Scots, they too had a historical link with the Imperial court of Augustus. Other nations, naturally, could claim similar connections , but for Scotland, marginalized by poverty, geography, and religious schism, this sense of being part of mainstream European culture was vitally important. Scottish artists, in particular, were to become enthusiastic Europeans – indeed, in Rome’s principal art teaching establishment, the Academy of St Luke, Scots students outnumbered every other nationality, with the exception o0f the Italians, during the middle of the century. Unusually, the Italians not only tolerated this cultural colony; they also offered it support in the form of patronage and acclamation. In part this may have resulted from the well placed influence of that other Scottish presence in Rome, the exiled jacobite court, but it hardly explains, for example, the extraordinary regard in which the neoclassical artist Gavin Hamilton was held in Rome, where his influence on the artistic life of the city was considerable, or the fact that Piranesi chose to dedicate a volume of his great Vedute di Roma to Robert Adam, or that Jacob More was the favoured artist of Prince Borghese.

Neoclassicism may have been derived from antiquity, but it was a living cultural force, and its influence on artistic and architectural taste was profound. In Edinburgh, a city intent on recreating itself on an unprecedented scale , it was embraced with unbridled enthusiasm in the greatest planning project ever undertaken in Scotland – the realization of James Craig’s winning competition entry for the New Town. Their appetites already whetted by the success of the Southside extensions, which had been underway for a decade, the city’s builders and developers were quick to buy up the feus as they became available, until demand reached the point where the original ‘first’ New Town of 1767 had to be extended to the north, east and west. The impetus to develop on a massive scale was passed down to the next generation, having continued with no significant interruption throughout the French Wars (it has even been suggested that suitably skilled French prisoners were pressed into service as craftsmen). By the 1820s William Henry Playfair’s magnificent scheme for yet another New Town connecting Edinburgh with its port of Leith ( with a ‘Mall’ which would have replaced modest Easter Road with something akin to the champs Elysees) was underway, but eventually civic ambition was to be thwarted by economic reality when, in August 1833, the city was declared bankrupt with debts in excess of $400,000. The Augustan dream had ended.

Even so, the scale of development which followed the first breach of the medieval town wall in 1757 had been enough to sustain a boom of some 75 years which had provided extraordinary opportunities for the building trades and related crafts. In its way, Edinburgh became something of a laboratory, not just for architectural theorists, but for enterprising artisans and businessmen who could see the opportunities to establish new methods of production for such things as architectural components. Clearly, the sheer quantity of, say, doors and window shutters required in the peak years of the early 1820 necessitated what we would call today a ‘fast-track’ system of manufacturing to a high standard. Whether these fittings were factory assembled or made on-site, there can be no doubt that in the vast majority of cases only quality of the highest order was tolerated – the evidence, after all, is still with us.

The same sort of regime must have been applied to timber and gesso chimneypieces, for it is as difficult to find an inferior Adam fireplace as it is to find a badly made paneled door of the same period. The skills involved were those of the carpenter, and the plasterer, while the design of the bas-relief was obviously entrusted to a draughtsman-artist of considerable ability. Both Robert and James Adam were particularly accomplished chimneypiece designers, but – as the Haworth brothers at the Carron Ironworks, or with Matthew Boulton, who designed neoclassical knobs and escutcheons for Adam – it is likely that high quality design work was produced to their general specification, or under the watchful eye of the firm’s Scottish ‘architect-locum’, James Paterson. The earlier limewood carved ornamentation on chimneypieces produced in the 1760s, which often had heavier mouldings reminiscent of William Adam’s period, could certainly have been designed within the Adam drawing office in the Cowgate, but after 1770, when neoclassical chimneypieces were required in large numbers, it is highly probable that they were designed ‘out of house’, perhaps, initially, with a high degree of Adam involvement. Since there is no documentary evidence for this theory, it can only be speculative, though the occasional appearance of the initials ‘R&F’ on a number of designs which probably post-date the Adam period suggest that at some time around 1800 an atelier existed in either Edinburgh or Leith which produced large numbers of chimneypieces with applied relief in a neoclassical format, but with certain stylistic innovations of a picturesque and sentimental nature based on contemporary themes.

It seems likely, given the consistency of a number of design features which had become common in the 1770s, that ‘R&F’ either were, or had taken over, the workshops which had been around in the Adam period, though whether the brothers would have classed a scene of hounds pursuing a fox in front of a triple spired gothic church as compatible with their ‘corrected’ style of architecture based on close study of Roman fragments is rather open to question. Other less-than-strictly classical subjects included a tousle haired boy in modern costume sitting on a tree stump with his ‘harried’ bird’s nest, surrounded by a number of sheep, three young ladies, in fashionable dresses dancing to the music of a young man’s pipes, and an elegant maiden leaning on an anchor surrounded by seashells and delicate fronds of seaweed. In some cases, the choice of subject was perhaps more than merely decorative. It has, for example, been suggested that the three dancing ladies were the Gunning sisters, celebrated beauties of the time, while interpretations of the lady with the anchor range from Britannia lamenting her lost sailors to Emma Hamilton in mourning for Lord Nelson. ‘R&F@ were, in effect, utilizing the fashionable strictures of neoclassicism as the aesthetic component of a new kind of folk art which appealed directly to popular sentiment. The discipline of proportion, the careful symmetry, were still adhered to, but another element was asserting itself – perhaps the first inkling of the ‘every picture tells a story’ predilections of the Victorians. Whoever those responsible were, this infusion of the contemporary picturesque into the strict regularity of ‘chaste’ neoclassicism expressed a flair and talent which was well beyond the ordinary, and even, at times, a sense of fun. This is not to say that the Adam brothers were themselves unwilling to break with the formal strictures of neoclassicism – the popular, if un-Roman ‘Thistle & Rose’ design, ideally suited to Edinburgh’s status as a sort of Hanoverian-Whig buffer zone, seems to have been designed by the 1770s, presumably with their blessing. Political iconography of this sort was nothing new – their father had created a ‘secret’ Jacobite design for Duns House in Angus in 1730.

In the absence of contemporary accounts or references the identity of the firm ‘R&F’ can to some extent only be guessed at, but it is highly likely that it developed as an off-shoot of an ornamental plasterwork company owned by James Ramage which, in the first years of the 19th century, occupied premises in West Jamaica Street Lane in the New Town. Both Ramage and his son ran a flourishing business, the latter being commissioned in 1822 to provide neoclassical plasterwork for Holyrood Palace throne room in readiness for the visit of George IV. While nothing of this scheme survives, elements of the highly ornamented ceiling in the younger Ramage’s own New Town flat seem to have been taken directly from it. No documented link between the Adam practice and a plasterer by the name of Ramage has, as yet, come to light,, but it is difficult to imagine Ramage senior, as a young man, working in ornamental plaster and stucco work in Edinburgh without coming to the attention of the firm. The Adam family practice was a major employer in both Scotland and England according to David Hume, writing to Adam Smith in 1772, when the financial crisis brought about by the speculative Adelphi scheme in London was threatening to bring the company down, about 3,000 jobs were at risk. It is not clear how many of those involved were actually on the payroll of the brothers’ development company, William Adam & Co, rather than in the employment of firms which depended on the company for regular commissions, like the stuccoists and plasterers Joseph Rose & Co, used extensively by Robert Adam on his English country houses. It is well known, however, that all the Adam brothers worked in close association with their craftsmen, and took a close interest in technical developments. This, again, was part of the debt they owed to their resourceful father who, in 1725, could write that he had ‘gott in to a Curious Secret, by a Swedish Gentleman, One of Our philosophy Masters who had dealt in that of Stucco formerly’ whereby he could produce a plaster-based compound with the hardness of marble.

Given this background, it is perfectly possible that the young James Ramage, perhaps after a suitable period of schooling in the Trustee’s Academy, was producing technically and aesthetically sophisticated work for Adam related projects in and around Edinburgh. Since the practice also provided commissions for several painters and artist-craftsmen of international repute, from the sculptors Michael Rysbrack and Joseph Wilton to the painters Michaelangelo Pergolesi, William Hamilton, and Angelica Kauffmann and her husband Antonio Zucchi, it followed that standards of design in the practice were amongst the highest available, and the caliber of training would inevitably reflect this.

Ramage, accordingly, - if he was involved in work for the Adams – would have been exceptionally well placed to set himself up as a producer of cast ornament in ‘Adam’s composition’, probably using moulds of either boxwood (said to be a Swiss development) or, possibly in the later period, of copper – certainly the boy with the bird’s nest, dating possibly from around 1810, was cast from a copper mould which was still in the possession of a Haymarket based firm, Scott’s, in the 1960s.

This possibly explains one half of ‘R&F’; so what of the other half? Some years ago an Edinburgh antique dealer was informed by a furniture historian that he had come across the words ‘Ramage and Ferguson’ written on the back of a timber chimneypiece. Subsequently the occasional pine and gesso neoclassical chimneypiece appearing at auction would carry this attribution – to all intents and purposes the mystery had come to an end. If Ramage was responsible for the cast gesso ornamentation, then Ferguson, it could be reasonably assumed, owned the carpenter’s shop which produced the timber frames.

The problem is, firstly, that there is no trace of this firm in the contemporary Edinburgh trade directories, no known reference to them in builders’ or architects’ account books of the period, and no surviving catalogues which might have offered customers a choice of designs – a strange omission if there was a company of that name manufacturing fashionable chimneypieces in such quantities (by one estimate there must have been more than 30,000 Scottish pine and gesso chimneypieces made in total.) Then secondly, to complicate matters further, a firm of shipbuilders appears in Leith towards the end of the 19th century bearing precisely the same name. In his 1897 history of Leith, James Campbell Irons listed the principal shipbuilding firms of Leith as ‘Messrs Ramage & Ferguson, Mssrs Hawthorn & Co, and Mssrs Morton & Co’. To Ramage and Ferguson, indeed, goes the credit for building what was purported to be the world’s largest sailing vessel (Copenhagen, for the Royal Danish Navy). At some point around 1930 the firm was taken over by shipbuilders Henry Robb & Co, Leith’s last shipbuilding yard, which went out of business in 1983.

Thus it is possible that Ramage & Son, plasterers, of West Jamaica Street Lane, joined forces with a carpenter by the name of Ferguson to manufacture elegant neoclassical chimneypieces for William Adam & Sons, architects, and then, with bankruptcy of the latter firm in 1801, went on to develop the theme by introducing such picturesque features as the boy with the bird’s nest panel, and Britannia (or Emma Hamilton) mourning on her anchor, as well as various fox hunting scenes, views of the Carlton Hill, snapping alligators, baskets of flowers, and virtually anything else that catch the fancy of the Regency public. This output was perhaps steady and successful until the crash of 1833, when local demand, at least, slackened. While Ramage & Sons were to be listed as plasterers well into the Victorian period, the ‘R&F’ chimneypiece seems to have disappeared as a product. Could it be that the partnership continued in some other form, finally to re-emerge as shipbuilders in the 1870s? If so, one is tempted to speculate quite how they held body and soul together during the intervening forty years.

It is also possible that the ‘R&F’ initials which feature on a handful of chimneypieces have no connection with the Leith shipbuilders, and that the ‘Ramage & Ferguson attribution arises from simple confusion. It could, indeed, have been the case that there was no single firm manufacturing chimneypieces, but simply a trade in cast decoration which could have been sold to any one of a number of carpenters. Certainly, there was an export trade in cast ornamentation to the United States by the turn of the century, when Robert Wellford’s ‘American Manufactory’ set up its own production line, with some home-grown subjects as ‘The Battle of Lake Erie’.

The early pine and gesso chimneypiece industry in Edinburgh, however, remains tantalizingly mysterious. Perhaps, since they represented fashion on a budget, and were considerably less expensive than the marble equivalents which they often simulated, they were not regarded as glamorous status symbols. To our eyes, they may seem like works of art; in the Edinburgh of Robert Adam, on the other hand, where excellence was the norm, they were standard architectural fixtures. They certainly went out of fashion, though from time to time there were ‘Adam revivals’ which brought them back into favour, and even produced a crop of late Victorian and Edwardian copies. Until as late as the 1960s they were regarded as almost valueless – during the demolition of St James’ Square (built in 1773) those not rescued by enterprising antique dealers were thrown out of windows before being dragged onto bonfires, while a fine example in a terrace of late 18th century houses belonging to the Art College (successor of the original Trustee’s Academy) was sold for the princely sum of £8, including grate and marble slips! Is it surprising, given this level of interest, that all knowledge of their origins two hundred years previously was lost?

It may – and in all likelihood will – be that in time to come some item of documentary evidence will emerge, and light will be shed on a manufacturing industry which, in its heyday, was obviously successful and much patronized, but until then the mystery of who was responsible for the design and manufacture of these perfectly crafted architectural creations will remain just that – a mystery.

David Black